In contemporary debates that bridge philosophy and empirical inquiry, the notion of political context emerges as a critical lens. It is not merely a backdrop against which scientific facts are discovered; it actively shapes the questions we ask, the methodologies we adopt, and the interpretations we grant to data. Within the framework of konstruktionizmus—a philosophical stance that emphasizes the constructed nature of knowledge—political context is inseparable from the very architecture of understanding. The present article explores how this intertwined relationship between politics and science has been reframed in modern philosophy, paying special attention to the ways that political forces inform the construction of scientific knowledge.

Origins of Konstruktionizmus and Its Political Sensitivity

Konstruktionizmus traces its intellectual roots to the early 20th‑century Vienna Circle, yet it extends far beyond the logical positivists. The movement emerged from a desire to clarify the foundations of science while acknowledging that every scientific claim rests upon a network of conceptual, methodological, and cultural assumptions. These assumptions, it was argued, are not natural givens but are socially constructed. Thus, the political context—be it the ideology of a governing body, the allocation of research funding, or the prevailing social values—directly influences which questions are deemed legitimate and which data are considered credible. By recognizing politics as a constitutive element, konstruktionizmus provides a tool for interrogating how power dynamics are embedded in scientific practice.

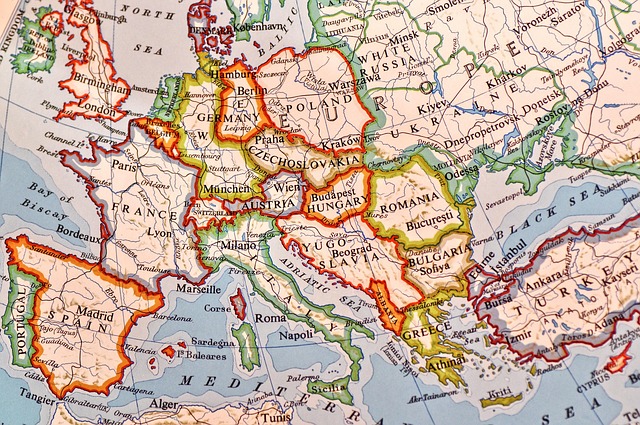

Political Context as a Determinant of Scientific Priorities

When governments allocate budgets for research, they send a powerful signal about what knowledge is valued. In countries where public health is prioritized, epidemiological studies receive substantial support, whereas nations focusing on industrial development may emphasize materials science and engineering. This allocation reflects more than fiscal capacity; it reflects a deliberate choice that shapes the trajectory of scientific discovery. Political context, therefore, not only influences funding but also dictates regulatory frameworks that determine ethical boundaries, publication norms, and data sharing practices. The interaction between political will and scientific agendas exemplifies how politics actively participates in knowledge construction rather than merely reacting to scientific outcomes.

Regulatory Bodies and Scientific Ethics

Regulatory agencies, often established by law, codify standards for research ethics, safety, and environmental impact. These standards are products of public policy debates and reflect societal values at the time of their inception. For instance, the adoption of the Belmont Report in the United States emerged from a national conversation about human rights and informed consent, deeply influenced by the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Similarly, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) imposes stringent data privacy requirements that directly affect how researchers design studies involving human subjects. The existence of such frameworks demonstrates how political context operationalizes normative expectations into concrete scientific protocols.

Modern Philosophy’s Critique of Scientific Objectivity

Recent philosophical discourse challenges the classic claim that science can achieve objective truths detached from human perspectives. Scholars argue that the interpretive act—how we read data, formulate hypotheses, and synthesize findings—is inherently value‑laden. Modern philosophy therefore invites scientists to adopt a reflective stance, recognizing that their own assumptions, including political biases, shape research outcomes. This perspective aligns with the konstruktionizmus emphasis on context, encouraging a dialogic relationship between the philosopher and the scientist. By foregrounding political context, modern philosophy reframes the scientific method as a socially embedded practice rather than a purely rational procedure.

Epistemic Relativism versus Political Pragmatism

One of the key debates within modern philosophy concerns the balance between epistemic relativism—the idea that knowledge is relative to cultural or individual perspectives—and political pragmatism, which emphasizes actionable solutions within existing political structures. While epistemic relativism cautions against claiming universal truths, political pragmatists argue that practical governance requires coherent frameworks. Konstruktionizmus serves as a middle path by acknowledging that knowledge is constructed within political contexts but still seeks to establish shared criteria for validity. This nuanced stance allows scientists and policymakers to collaborate without surrendering to relativistic skepticism or rigid positivism.

Case Study: Climate Science and Public Policy

The global discourse on climate change exemplifies how political context informs scientific interpretation and vice versa. Scientific consensus on anthropogenic warming has evolved through a series of peer‑reviewed studies that incorporate data from satellites, ocean buoys, and atmospheric models. Yet, the reception of these findings varies dramatically across political spectra. In some regions, political leaders emphasize economic growth over environmental regulation, framing climate science as a threat to industrial competitiveness. In others, environmental legislation is enacted to mitigate emissions, illustrating how political agendas shape the adoption of scientific recommendations. This reciprocal relationship underscores the necessity of incorporating political context into scientific communication and policy development.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration and Governance

Effective climate policy requires coordination between scientists, economists, sociologists, and political actors. Interdisciplinary panels—such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—exemplify how political context can shape scientific synthesis. The selection of experts, the weighting of uncertainties, and the framing of scenarios are all influenced by the political institutions that sponsor these panels. Consequently, the resulting reports are not merely scientific artifacts but negotiated documents that reflect the priorities and power dynamics of the global community. The political context, therefore, becomes a co‑author of scientific narratives, challenging the illusion of pure objectivity.

Challenges and Critiques of Konstruktionizmus

While konstruktionizmus offers a robust framework for understanding the interplay of politics and science, it faces several criticisms. Critics argue that an overemphasis on social construction may lead to relativism that undermines scientific progress. Others claim that political context is too diffuse and variable to provide a stable analytical ground. Additionally, skeptics contend that konstruktionizmus may obscure the role of natural laws and empirical evidence that appear to transcend political influence. Addressing these concerns requires a careful balance: acknowledging the influence of politics without discarding the rigor and predictive power of scientific methods.

Methodological Strategies to Mitigate Bias

- Transparent peer‑review processes that disclose potential conflicts of interest.

- Multi‑institutional funding mechanisms that reduce dependence on single political bodies.

- Interdisciplinary ethics boards that include representation from diverse political perspectives.

- Open data policies that allow independent verification and reinterpretation of results.

These strategies demonstrate that konstruktionizmus is not merely a theoretical critique but offers actionable steps to align scientific practice with democratic ideals.

Future Directions: Toward a Democratic Science

The integration of political context into modern philosophical analysis points toward a future where science is not only a technical enterprise but a democratic public good. Initiatives such as citizen science projects, participatory budgeting for research grants, and public deliberation panels are emerging as models that embed political engagement directly into the scientific process. By harnessing these mechanisms, the scientific community can ensure that research agendas reflect broader societal values, thereby strengthening the legitimacy and relevance of scientific knowledge.

Educational Reform and Public Literacy

Educating future scientists and citizens about the political dimensions of scientific practice is essential. Curricula that integrate philosophy, ethics, and policy studies with laboratory work can foster a holistic understanding of how knowledge is constructed. Public science communication, through accessible language and contextual framing, can help demystify the role of politics in science, promoting informed civic participation. As the boundaries between knowledge creation and political decision‑making become increasingly porous, such education will be indispensable for sustaining a healthy democratic society.

Conclusion

Political context is not a peripheral concern but a central component of how scientific knowledge is produced, interpreted, and applied. Konstruktionizmus invites us to view science as a socially and politically situated enterprise, encouraging critical reflection on the values and power structures that shape research. Modern philosophy’s engagement with these ideas deepens our understanding of the reciprocal relationship between politics and science, offering pathways toward more inclusive, transparent, and democratic scientific practices. As we confront complex global challenges—climate change, pandemics, technological governance—the integration of political context into scientific discourse will remain vital for ensuring that science serves the public good in an equitable and just manner.